THE SILENT STRENGTH OF THE SKIES

The women of the airship service during the Great War

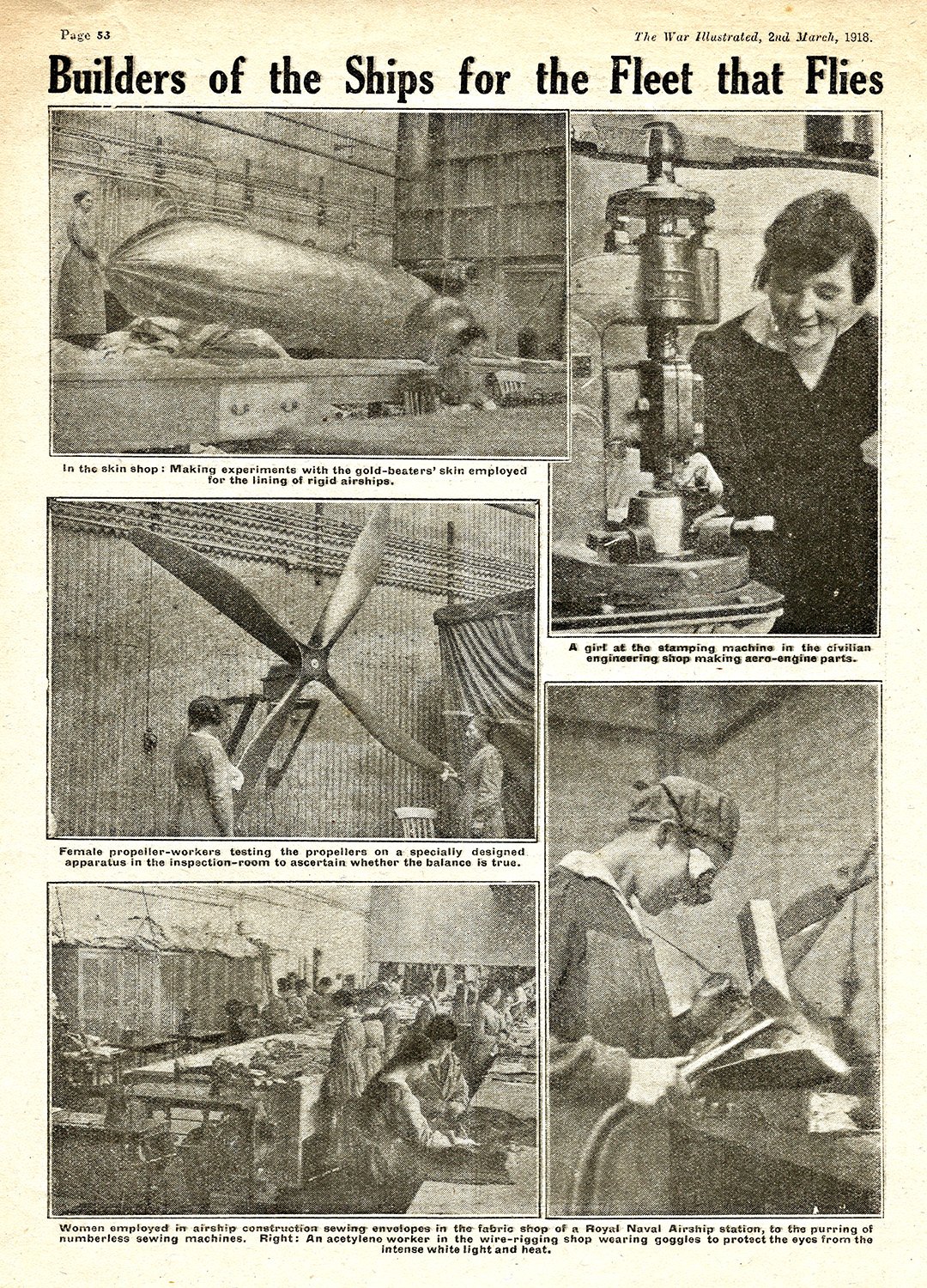

When most people imagine the role of airships in the Royal Naval Air Service and Royal Air Force during the Great War, their minds go to the crews who braved the skies in fragile airships, scanning the seas for German U-boats. But behind the airships and the men who flew them was a quieter force – the women who made the entire operation possible.

The Royal Naval Airship Service (RNAS), later incorporated into the Royal Air Force, relied on a vast network of workers on the ground. As the war dragged on and manpower shortages grew acute, women stepped into roles that were once considered far beyond their reach. Their contribution was not merely supplementary – it was essential.

New officer recruits to the Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS) officers, wearing a mix of civilian dress and uniform, undergo drill at Crystal Palace during the First World War. Image: IWM/Wikimedia Commons.

In November 1917, facing critical manpower shortages, the Admiralty inaugurated the Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS). Initially numbering around 3,000, the Wrens would soon work across over 100 roles.

At first, women in the RNAS were seen in familiar wartime roles: seamstresses, clerks, and canteen workers. But the demands of airship operation soon expanded their responsibilities. Directed by Dame Katharine Furse, the service rapidly evolved beyond clerical and domestic duties to include technical support – wireless telegraphists, code operators, and electricians and mechanics.

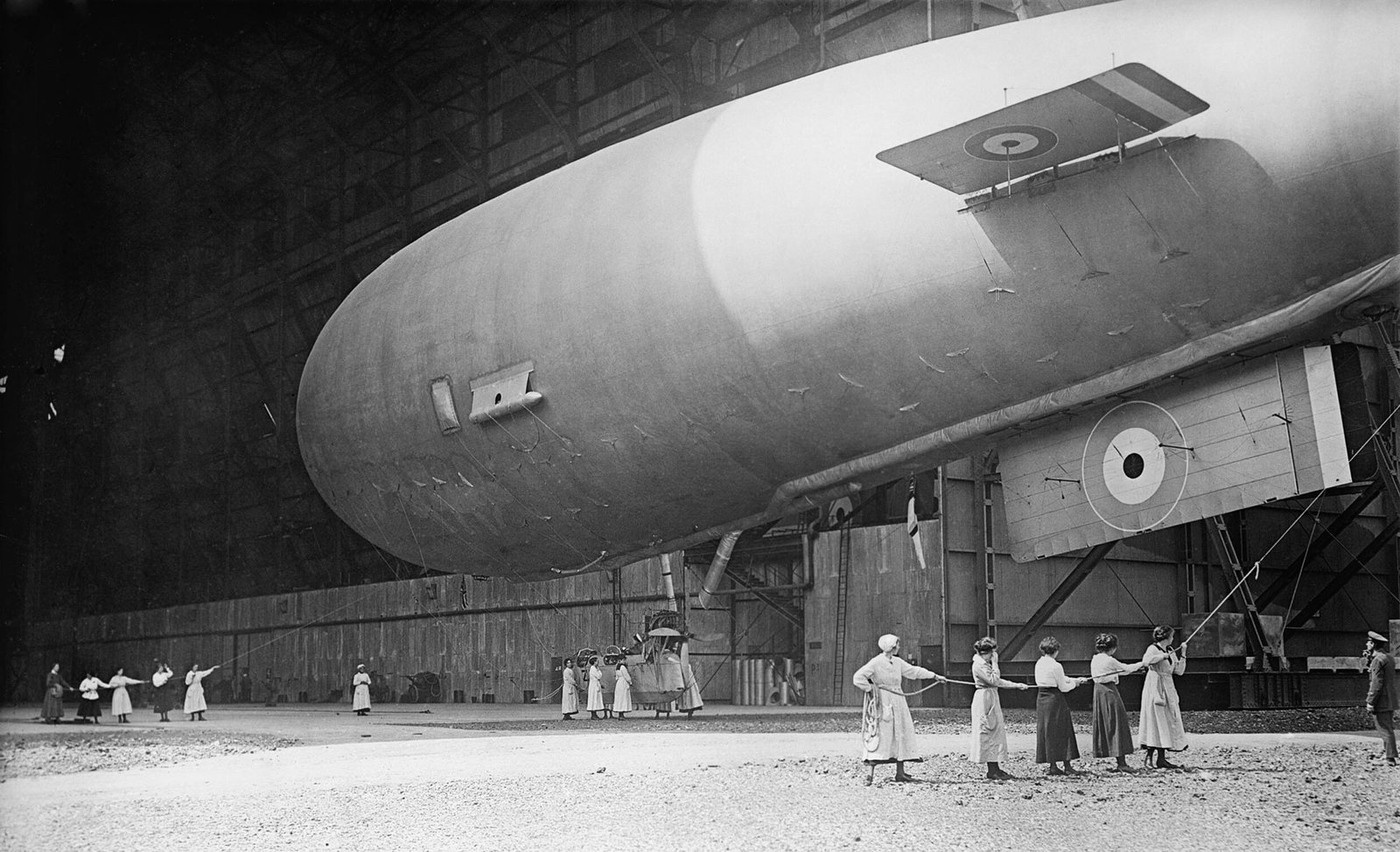

Airships required constant maintenance, and handling these immense craft was no small feat. When the vessels came in to land, it took dozens of people to haul them safely to ground. Increasingly, women were part of those rope teams, their physical strength and discipline every bit as vital as their male counterparts.

At stations such as Kingsnorth, Pulham, and East Fortune, women could be seen in overalls, mud on their boots, wrestling guide ropes or helping secure mooring blocks. Newspaper reports at the time marvelled at the sight of “girls in khaki” hauling on lines as if it were the most natural thing in the world.

Women handling Sea Scout Zero (SSZ) airship at Howden. Image: IWM/Wikimedia Commons.

Beyond the brute strength of ground-handling, women also played critical roles in technical work. They became skilled in fabric and dope workshops, repairing the massive envelopes of the airships. The fineness of their stitching – often compared to surgical skill – helped ensure that the craft stayed airtight and safe. Others were trained in signalling, meteorology, and administrative duties, becoming an indispensable part of the highly co-ordinated system that kept the airships patrolling day and night.

The Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS), formed in 1917, formally recognised the scale of women’s contribution. Wrens were posted to airship stations across the country – their presence freeing up thousands of men for front-line duties – a contribution that was quietly, but profoundly, strategic.

The Women’s Royal Air Force (WRAF) was created on 1 April 1918, the same date as the Royal Air Force. Women’s Royal Naval Service were invited to join the new WRAF. The minimum age to join was 18 and, in order to join, women had to pass a medical examination and to provide a satisfactory reference.

Some of the women of Pulham Air Station with the tools of their trades. Of the 143 WRNS records at Pulham, women served as fabric workers, riggers, clerks, cooks, drivers, telephone operators, even pigeon-women and armourers. Interestingly, at centre front is a seat cushion form an NS-Class airship. Image: The Pennoyer Centre.

Nellie Crickmore was based at Pulham Air Station when N.S.11 was lost in 1919. Find out more about her story. Image: NS11.org

After the Armistice: Demobilisation and Change

When the guns finally fell silent in November 1918, Britain began the vast process of demobilisation. For the women of the airship stations and the wider WRNS, it was a bittersweet moment. Their work had been vital, their contribution undeniable, yet by the spring of 1919 the service was formally disbanded. The WRNS was considered a wartime measure, not a permanent branch of the Navy. Thousands of women were thanked for their service—and then dismissed, their uniforms folded away, their roles handed back to men returning from the front.

The situation was mirrored in the newly created Women’s Royal Air Force (WRAF), which absorbed some former RNAS staff after the Air Force was established in April 1918. By 1919, the WRAF too was rapidly wound down, its members demobilised and told to resume civilian lives.

For many women, the return to pre-war expectations was a shock. They had proven their capability in roles ranging from technical maintenance to signalling, and they had experienced a camaraderie and independence that would have been unthinkable in 1914. To be told, in effect, that their service was no longer required, was disheartening. Some felt a keen sense of loss—of purpose, of community, of recognition.

Women of the WRAF at rest. Image: IWM – Q 84859

Yet the legacy of their service was profound. In a few short years, women had demonstrated that they could master skilled, technical, and physically demanding roles. They had shared the risks of war, worked in disciplined service alongside men, and shown themselves equal to the task.

Though the WRNS and WRAF were disbanded in 1919, their memory lingered. When Britain again faced the threat of war in 1939, both organisations were re-formed, this time on a more permanent footing, and on a far larger scale. The foundations laid by the women of Pulham, Kingsnorth, East Fortune, and countless other stations proved invaluable.

Perhaps most importantly, the experience changed the women themselves. Many came away with new confidence, new skills, and new ambitions. They had glimpsed possibilities beyond domestic service and factory work. Even if society was slow to adjust, these women had helped open the door to broader horizons—for themselves, and for the generations who followed.