THE WAR ARTISTS

How art went to war with the NS-Class airships

During and after the First World War, the British government turned to artists as well as photographers to record the machinery and atmosphere of the conflict. Photographs could capture detail, but they could not always convey scale, drama, or the human response to new technologies.

Airships, then at the very forefront of aviation, became a particular focus. Artists such as Alfred Egerton Cooper and Sir John Lavery were asked to depict these giants of the air. Cooper, who trained as a painter before serving in the war, created images that highlighted the engineering detail and monumental presence of airships in flight and in sheds. Lavery, already an established portraitist and war artist, lent his refined touch to scenes of airships at rest, capturing not just machines but also the sense of national pride and anxiety they embodied.

The commissioning of such works was not only about producing accurate records; it was also about shaping public perception. By presenting airships through the eyes of respected artists, the authorities sought to convey a sense of innovation, power, and legitimacy to a public still grappling with the costs of war. Today, these paintings remind us that airships were more than military tools – they were symbols of a new age of flight, rendered permanent in oil and canvas.

Portrait of an Officer from the Artists Rifles (1917) – possibly a self portrait. Image: Wikimedia Commons.

Alfred Egerton Cooper (1883-1974)

Alfred Egerton Cooper studied art at the Bilston School of Art and at the Royal College of Art, where he received his diploma in 1911. He then worked as assistant to John Singer Sargent at his studio in Tite Street, Chelsea. Cooper exhibited at the Royal Academy forty times and became best known for his portraits – especially of Winston Churchill and the Royal Family.

At the start of WWI Cooper joined the 28th County of London Volunteer Regiment, the Artists Rifles. He was gassed and lost some sight in one eye. By the end of the war he was made official artist to the RAF and became an expert in the art and techniques of large scale aerial camouflage, sketching and painting landscapes from a variety of aircraft and airships. A newspaper from 1919 said, “Captain Cooper is different from all other air artists. Many men have pictured flying subjects from the ground, but he has taken his canvases and paints and brushes into the air and worked while flying. That he has been astonishingly successful – perhaps brilliantly successful is not too strong a thing to say – is there for all London to see and agree upon at present.” During September 1919 Cooper exhibited several works at Lady Sybil Grant’s Airships in Peace and War exhibition at the Prince’s Gallery, Piccadilly.

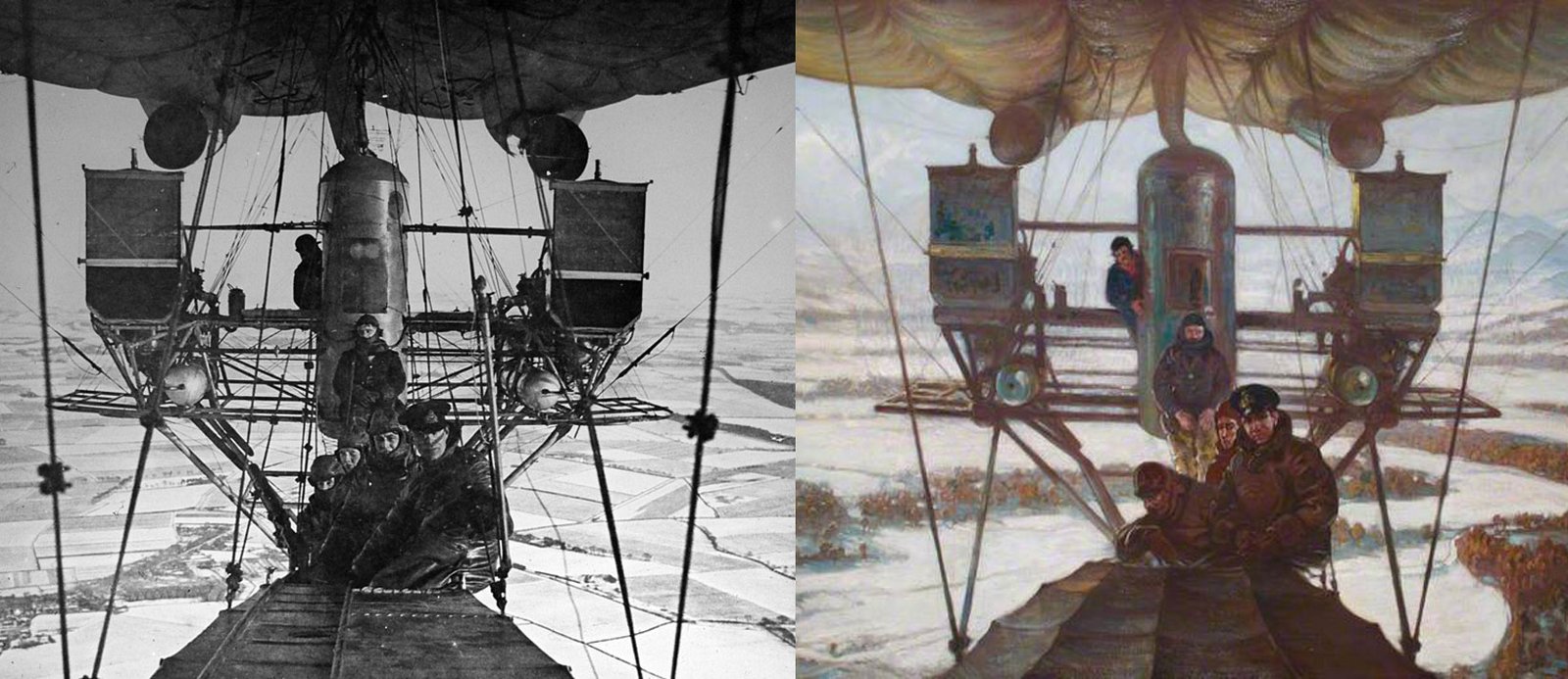

While we do need to undertake some more research into Cooper’s airship flights we do know, certainly for practicality’s sake, he did work from reference photographs. For instance, for his painting The First Snow, from the NS8 airship he almost certainly used a photograph taken on board N.S.4 as reference (the engine arrangement being completely different). There is also no mention of any passengers on the official logs for this period.

Comparision of photograph and detail of The First Snow, from the NS8 airship over the Lammermuirs, 1918 by Alfred Egerton Cooper. Artwork image: RAF Musuem Collection.

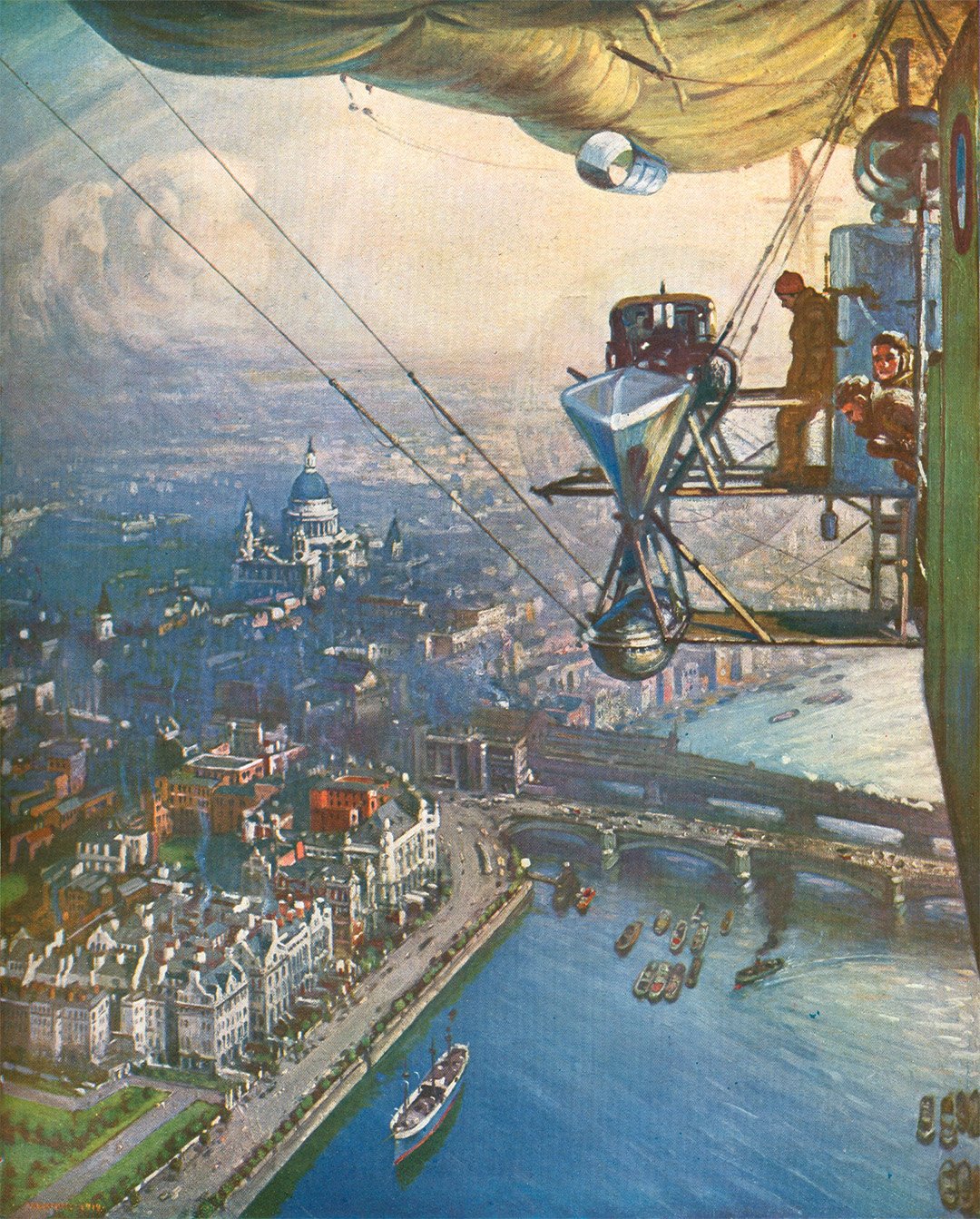

This striking image, painted by Alfred Egerton Cooper (1883-1974) was published in The Sphere magazine on 6 November 1920.

This painting is especially interesting as it shows NS11 above London. While it was fairly common for airships to be flown over the capital for official and semi-official reasons, it was the first record we found of NS11 being flown over London just a few weeks before the loss.

The caption for the picture reads:

London from an Airship

From a painting by Captain A E Cooper

This picture was one of the successes of the last Academy show. The artist has here pictured the outlook from one of the cabin windows of the airship “N.S.11.” Blackfriars Bridge, with its sister railway bridge, is seen spanning the river, whilst Temple lawns and trees are seen in the left foreground. The training ship “President” is seen floating off the Embankment, a vessel from which many naval volunteers passed for service at sea during the war. One the airship’s mechanics, it will be remarked, is precariously perched on one of the stays leading to the engine.

We can be more precise with the date this took place from the 17 July 1919 issue of Flight magazine which states that “It is with great regret that we have to record that the British non-rigid airship N.S. 11, which cruised over London a week or so ago, met with disaster in the early hours of Tuesday morning, while cruising off Morston, near Blakeney.”

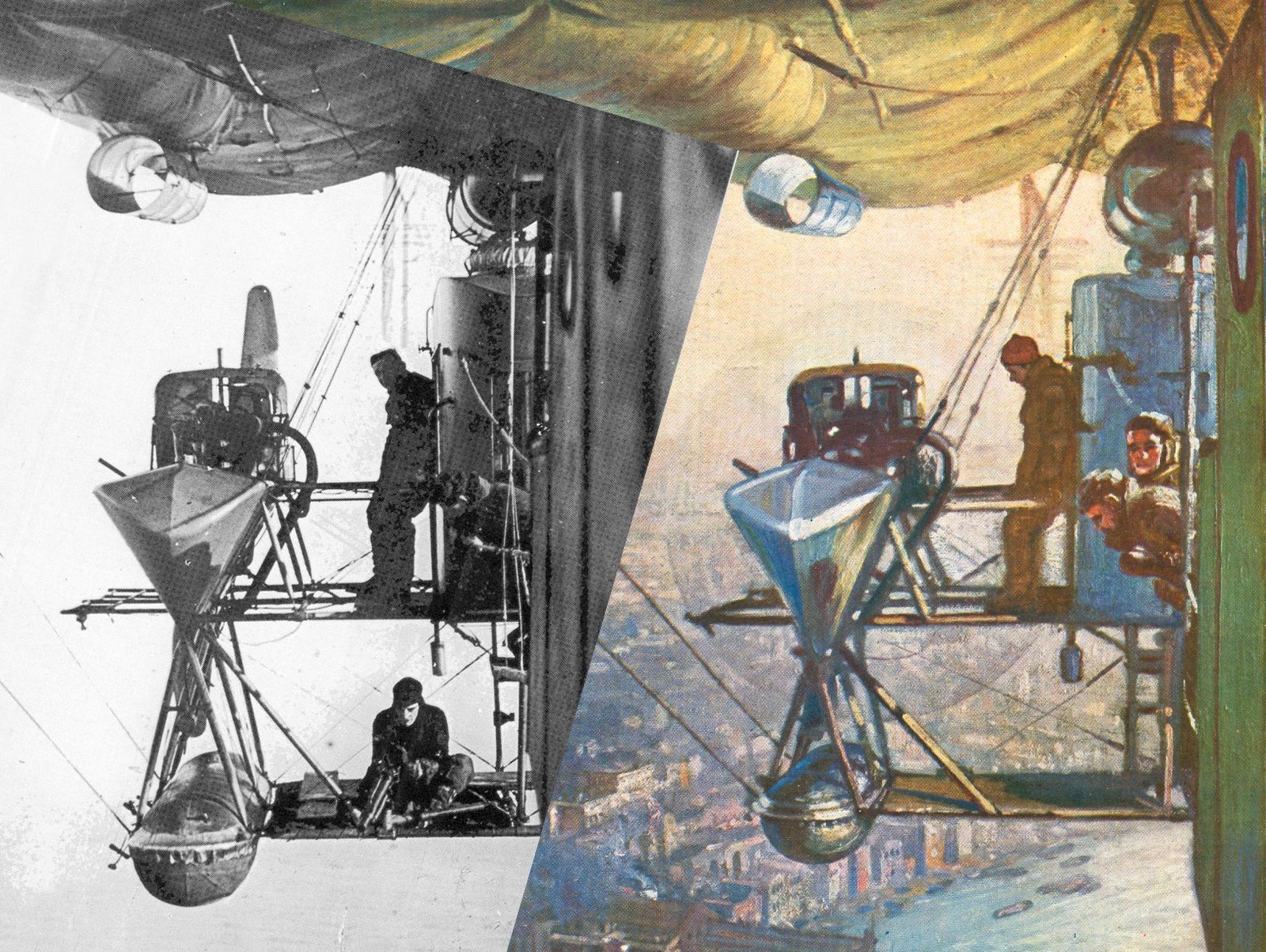

Comparisson of reference photograph of N.S.8 with Coopers depiction of N.S.11. Images: NS11.org collection

to create the majorpWe can confidently say that Cooper used a photograph for reference for the painting. This image shows the painting and photograph side by side. The gunner has been removed (quite understandably, while flying over London!), but so many of the details and reflections in the photograph have been included in the artwork.

As advised by Brian Turpin, we do know that the refernce photograph is highly likely to actually be N.S.8, which was fitted with a Vickers 1.59′ aero gun as depicted. N.S.11’s flight over London took place during a gap in the official logs for N.S.11, so we can’t say for sure if Cooper was on board for this flight.

The original painting is now in the Cranfield University Collection. More of Cooper’s work can be found at the Imperial War Museum and the National Portrait Gallery.

As an accomplished artist, Cooper certainly didn’t need to work from reference photographs to create the majority of his works. Many of his airship paintings can be seen in the scenes depicting Barnes Wallis’ office in the film The Dambusters.

N.S.7 in a Shed, Alfred Egerton Cooper, 1918. Image: Wikimedia Commons

Naval N.S.7 over Fleet, Alfred Egerton Cooper, 1918. Image: Wikimedia Commons

Sir John Lavery (1856–1941)

An Irish-born painter renowned for his portraits and wartime depictions, Lavery was born in Belfast. He studied at Haldane Academy in Glasgow and later at the Académie Julian in Paris. He gained prominence in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, creating portraits of notable figures, including Winston Churchill and H. H. Asquith. His style evolved from early influences of the Glasgow School to a more Impressionistic approach, marked by vibrant colours and dynamic compositions.

During World War I, Lavery was appointed an official war artist. However, ill health and a serious car crash during a Zeppelin bombing raid prevented him from traveling to the Western Front. Consequently, he remained in Britain, focusing his artistic endeavours on subjects related to the Home Front. Lavery produced a series of paintings depicting boats, airplanes, airships, and naval vessels. One notable work is A Convoy, North Sea, 1918, which offers an aerial view from an airship looking down onto a convoy in the North Sea. This painting exemplifies Lavery’s ability to capture the scale and drama of wartime scenes from unique perspectives.

Lavery’s prolific wartime works are held in various collections, including the Imperial War Museum and the Ulster Museum. His contributions as a war artist offer a unique perspective on World War 1, focusing on the experiences and resilience of those on the Home Front. Through his paintings, Lavery captured the complexities of war beyond the battlefield, highlighting the technological advancements and the human spirit during a time of global conflict.

Perhaps Lavery’s best known depiction of an NS-Class airship is the painting A Convoy, North Sea, 1918. While certainly painted using several reference photographs we do know that Lavery visited East Fortune airship station in August, 1918, and made three flights in N.S.7 on 26th, 27th and 29th August with H C Fuller in command. He is listed by name in the crew list. The painting shows N.S.7 escorting a convoy, which it did on his three flights.