MEPHISTOPHELES

How the world record breaking N.S.11 connects to a world record breaking racing car

In the roaring early 1920s, speed and danger were inseparable, but few machines embodied both as completely as Mephistopheles, Ernest Eldridge’s audacious racing car. Built by shoehorning a Fiat A.12 aircraft engine into an ageing chassis, this machine was not just fast. It was terrifying.

Mephistopheles at the Goodwood Festival of Speed, 2013. Photo: NS11.org

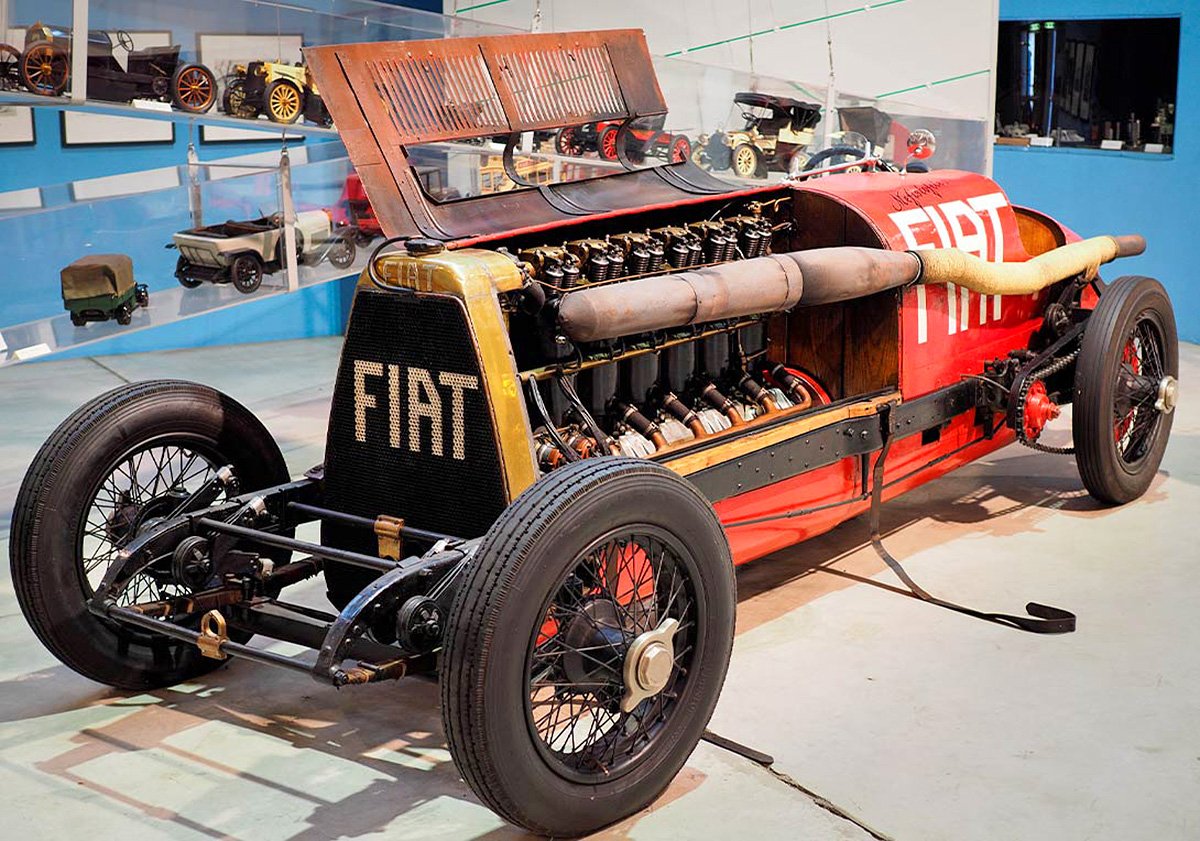

The car began life as a 1908 Fiat SB4 racing chassis, already a veteran of high-speed track work. Eldridge transformed it by installing a surplus Fiat A.12 “bis” aero engine, a six-cylinder, in-line, liquid-cooled giant used to power aircraft, and airships such as N.S.11, during the First World War. Displacing 21.7 litres and originally rated at around 245–260 horsepower, Eldridge’s modifications pushed the output closer to 300 horsepower at 1,800 rpm. To make it fit, he lengthened the SB4 chassis by nearly half a metre, reportedly using sections of London bus frame rails. The result was a monster: chain-driven to the rear wheels, with only rudimentary rear brakes, and saddled with tyres never designed to cope with such power.

The Fiat A.12 engine was already a legend long before Eldridge ever laid hands on it. During the war, it powered Italian and British aircraft with equal ferocity. And long before anyone thought of bolting an aircraft engine into a racing car, N.S. Class airships had already harnessed its brute strength, replacing the Rolls Royce Eagle engine which brought with it significant transmission issues. Where Mephistopheles carried a single A.12, N.S.11 ran with two of them. That meant double the size, double the power, and double the engineering challenge. The pioneers behind N.S.11 had already confronted problems of cooling, vibration, and raw mechanical stress that later haunted every post-war experiment in aero-engined racing. In a sense, N.S.11 had already shown the way.

When Mephistopheles first appeared at Brooklands in October 1923, it was still rough, still unpredictable. Eldridge faced constant problems: broken damper mounts, shredded tyres, and handling that bordered on the unmanageable. Yet the car had an undeniable presence. It began to set records, including a standing half-mile at over 77 mph. Then came the decisive test at Arpajon in France on 12 July 1924. With a new reverse gear added to satisfy regulations, Eldridge hurled Mephistopheles down a stretch of public road, recording a flying kilometre at 146.01 mph. It was a world land speed record—and the last ever to be set on an open public road.

Those who experienced the car spoke of it with awe and dread. Michele Lucente, who drove Mephistopheles decades later during a Fiat museum demonstration, confessed, “I am so busy with the steering, the gears, looking for the braking, there’s no time to think about what it is like. When I get out, my hands, they are shaking.” Jim Ames, Eldridge’s riding mechanic, remembered the sheer terror of clinging on while simultaneously pumping to pressurise the fuel tank and operating the oxygen supplement that fed the intake. Even starting the car was an ordeal. As one modern Fiat mechanic observed, “It takes slightly less time to start the Space Shuttle.” Smoke, flames, and violent coughing fits from the cylinders were part of the ritual before the engine’s thunderous boom shook the ground into submission.

Mephistopheles. Image: Centro Storica Fiat

Ernest Eldridge sits in the highly-modified FIAT SB4, powered by the Fiat A12 engine. The car is pictured at Brooklands in 1924. Image: oldmachinepress.com

Eldridge at the wheel of Mephistopheles at Arpajon, France for a land speed record attempt. Image: oldmachinepress.com

Behind this creation was a man as fascinating as his machine. Ernest Arthur Douglas Eldridge, born in 1897, was a gambler, adventurer, and restless innovator. After serving in the war, he threw himself into motor racing with a flamboyant disregard for convention. He experimented with aero-engined specials long before Mephistopheles, using Maybach and Isotta-Fraschini powerplants. His appetite for risk was matched only by his determination to win, whether at the racetrack or the card table.

What made Mephistopheles so terrifying was not only its speed but the conditions under which it was driven. The tyres of the era could barely cope with the forces. The suspension was crude, the chain drive brutal, and the brakes laughably inadequate. Heat and vibration stressed every component to breaking point, while the lack of protection left both driver and mechanic frighteningly exposed. To set records with such a machine required nerve of steel – and perhaps a touch of madness.

That is what ties Mephistopheles to N.S.11. Both were powered by Fiat’s immense A.12 engines, but where Eldridge wrestled with one, N.S.11 carried two, doubling the challenge for the crew.