THE AIRSHIP SERVICE IN WWI

Dirigibles in the Royal Naval Air Service and Royal Air Force

As war broke out across Europe in August 1914, Britain had very few military airships. While Germany had invested time, money and faith in airship development, Britain could muster only a handful of non-rigid and semi-rigid experimental craft—some of them foreign-built—and just 195 trained airship personnel. Germany, by contrast, entered the war with ten proven airships, shared between the Navy and the Army.

This disparity was not accidental. In the decade before the war, Count Zeppelin’s creations had captured the imagination of the German public, who flocked to see these giants of the air. Germany had become, as one observer put it, “the most airship-minded nation in the world.”

Its commercial carrier, DELAG, was founded in 1909 by the Zeppelin company and made over 1,600 passenger flights, covering more than 100,000 miles and transporting over 10,000 passengers by the outbreak of the war. This wasn’t just about technology – it spoke to a national mindset that saw airships as strategic, symbolic, and deeply embedded in both civilian life and military planning.

By 1914, military planners had already integrated Zeppelins into strategy as long-range scouts and potential bombers. Britain, by contrast, had remained cautious and under-invested, preferring to rely on its unmatched surface fleet and the promise of the aeroplane. The Admiralty’s hesitation meant that at the outbreak of war, Britain was badly behind.

DELAG Zeppelin route chart 1912-13. Image: National Air and Space Museum Archives

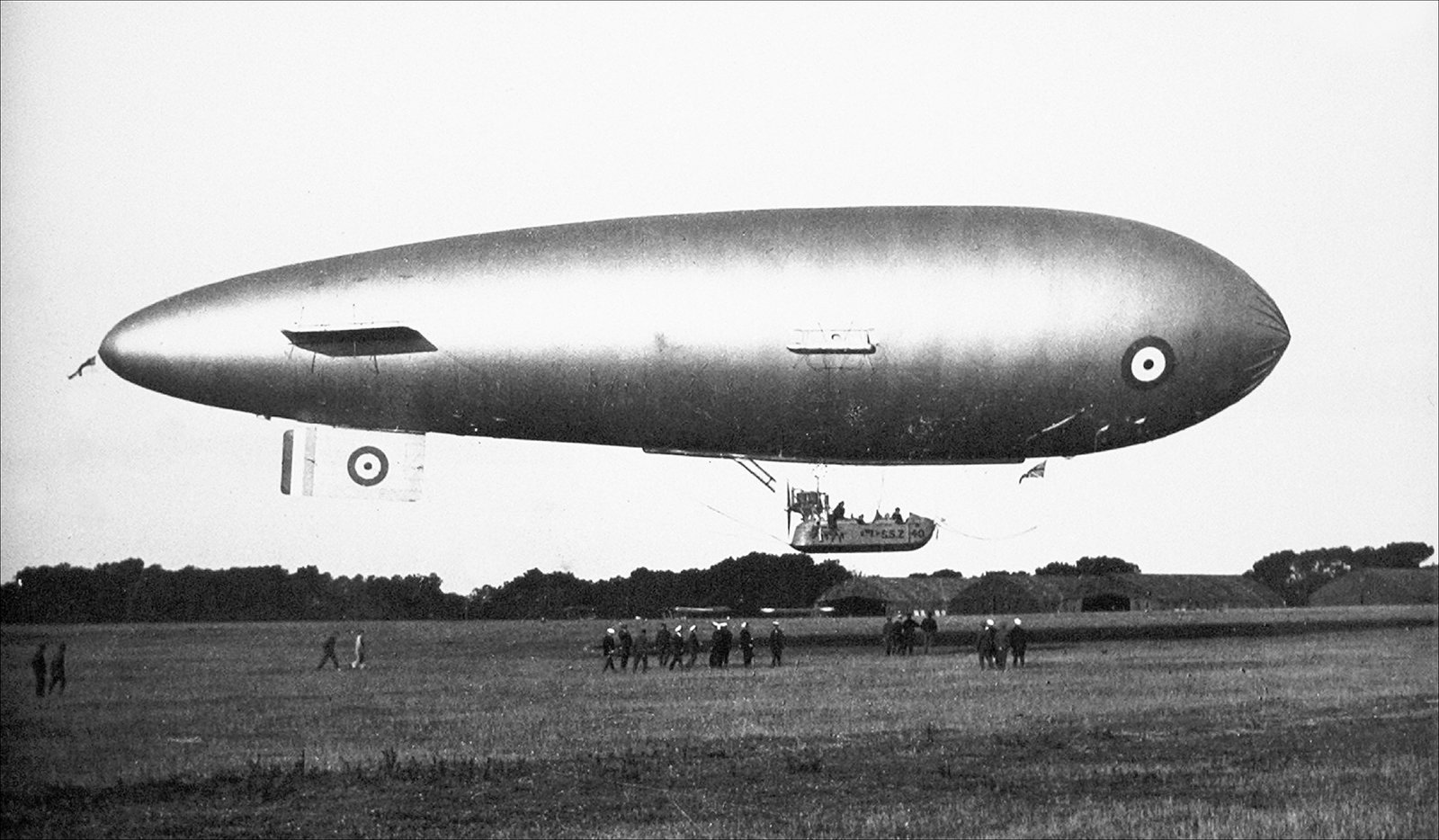

SSZ 40 at Mullion. Image: Brian Turpin

Air Commodore General Edward Maitland Maitland, 1918 – Director of Airship Equipment. Image: Flight Magazine/Wikimedia Commons.

From 1 January 1914, all British Army and civilian airships had been placed under Royal Navy command. Officers who distrusted the aeroplane – among them the brilliant Edward M. Maitland were allowed to transfer into the fledgling Airship Service. On 1 July 1914 this division officially became the Royal Naval Air Service, fully under Admiralty control. Yet even then, doubts persisted. One official report summed up the prevailing mood:

“… the policy of the Government with regard to all branches of aerial navigation is based on a desire to keep in touch with the movement rather than hasten its development. It is felt that we stand to gain nothing by forcing a means of warfare which tends to reduce the value of our insular position and the protection of our sea power.”[2]

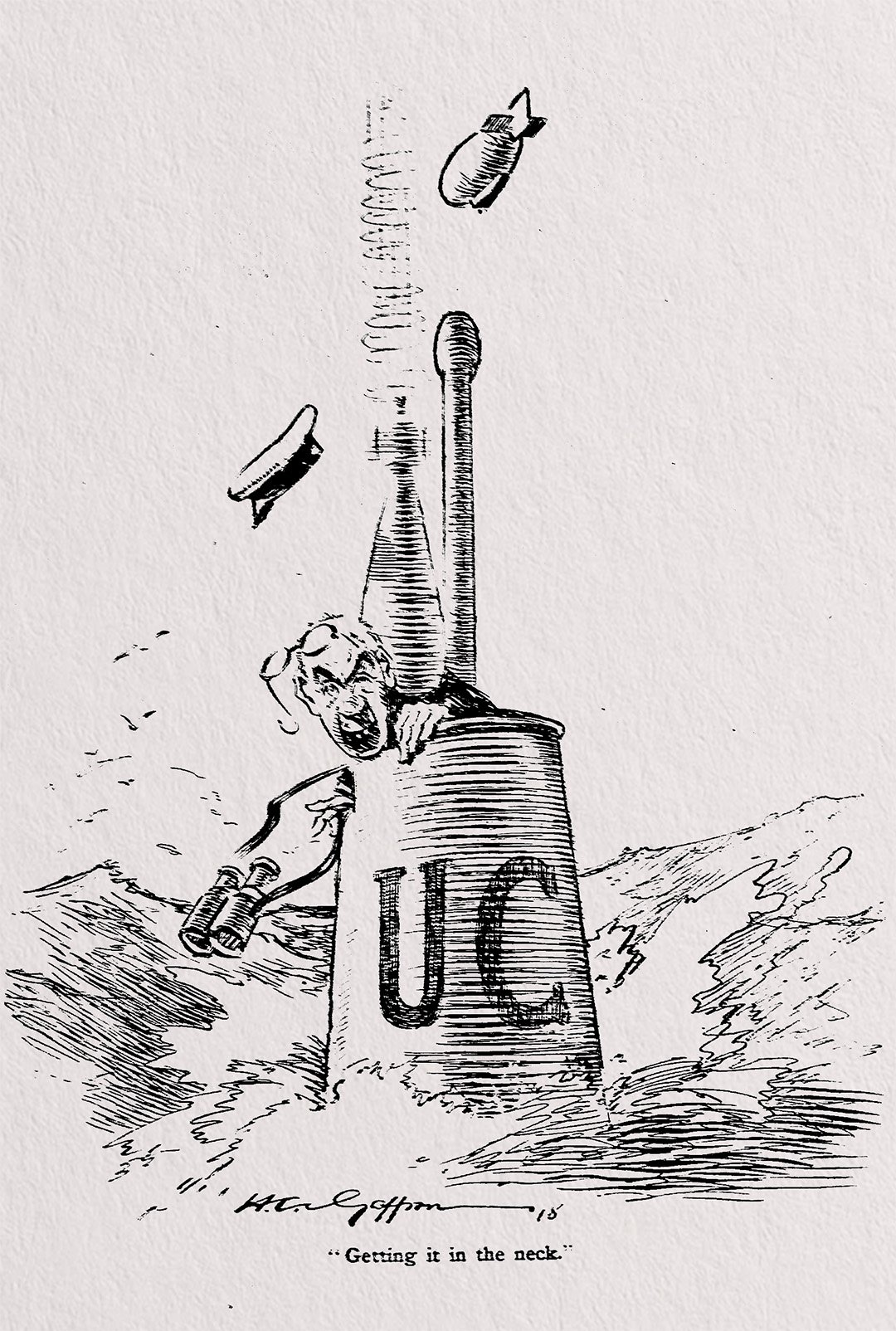

Those doubts soon met hard reality. By 1915, Germany had unleashed unrestricted submarine warfare. Its U-boats prowled the shipping lanes, attempting to strangle Britain’s lifeline of food and raw materials. In peacetime, over half of Britain’s wheat and much of its meat came from overseas; if merchant ships could not cross the Atlantic in safety, the nation risked being starved into submission.

Convory being escorted by an HS-Class airship. Image: IWM – Q 84607

Here the airship came into its own. As J. A. Sinclair later explained in his book Airships in Peace & War:

“Its hovering powers, its ability to remain in the air for days at a time, its independence of engine-power in an emergency – all these things combine to make an airship singularly suitable for reconnaissance, particularly over the sea, and it is in that sphere that the airship excels.”

Airships became one of Britain’s most effective counter-measures against the submarine. They patrolled the coastline, scouted for mines, escorted convoys and, above all, forced U-boats to submerge. A submerged submarine was far less dangerous, unable to attack shipping so freely. The point was made starkly in the log of a captured U-boat, which recorded simply: “Sighted airship – submerged.”

Airship crews became adept at spotting signs of lurking submarines – an oil slick on the surface, or gulls circling around the thin wake of a periscope. Remarkably, apart from a single exception, no ship was ever sunk by a U-boat while it was under the protection of an airship.

Over the four years of conflict, 225 new British airships were delivered. Together they flew 88,000 hours and covered more than two million miles. Losses were low: only 48 officers and men of the airship service were killed through enemy action or accidents.

Airships did attack and help sink U-boats on occasion, but their true value lay in deterrence. By denying Germany the freedom to prey on Britain’s lifelines at sea, they helped tip the balance of the war. As Patrick Abbott later concluded in The British Airship at War:

“The British airships did not win the war by themselves, but without them the war might never have been won.”

Cartoon from The Battle Bag, Longside’s monthly journal, January 1919. Image: RAF Museum.

R.34 at Mineola, New York, having just broken N.S.11’s endurance record. Image: Brian Turpin. Colourised by Art Lewry.

R.34 arriving at Pulham after its double-drossing of the Atlantic, 13 July 1919 – less than two days before the loss of N.S.11 flying from the same air station. Image: The New York Times/Wikimedia Commons

By the conclusion of the First World War, Britain’s initial skepticism towards airships had transformed into recognition of their strategic potential. While the early years of the war saw airships primarily as tools for coastal defense and anti-submarine patrols, the end of the conflict marked the beginning of a broader vision. Military leaders and engineers began to perceive airships not only as instruments of war but also as vessels capable of connecting the vast expanse of the British Empire.

This shift in mindset culminated in the ambitious Imperial Airship Scheme of the 1920s, aiming to establish regular air services between Britain and its dominions. The R34, which had successfully completed a historic double transatlantic flight in 1919, showcased the possibilities of long-range air travel and symbolised a new era in aviation. It demonstrated that British engineering could achieve remarkable feats, hinting at a future where airships might connect the far reaches of the Empire more quickly than ever before.

While the post-war period brought challenges and setbacks, including the later tragedy of the R101, the wartime experiences and pioneering flights of the R34 had already cemented airships as a transformative force, both militarily and symbolically, in Britain’s evolving vision of global reach.

- Airships in Peace & War, J. A. Sinclair, 1934

- Ibid

- The British Airship at War, Patrick Abbott, 1989